|

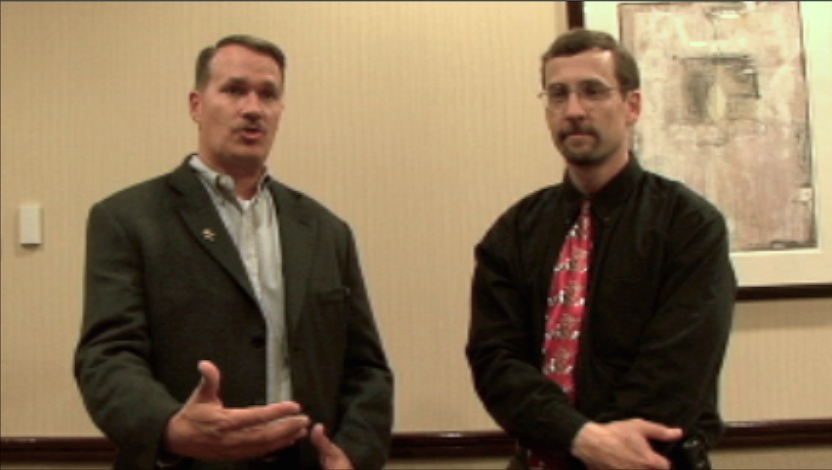

Greg Hilmas and Bill Fahrenholtz, both professors at Missouri S&T, are working on developing ceramic materials that can withstand ultrahigh temperatures (1,600°C–3,000°C) that will be encountered by hypersonic planes of the future. Ultrahigh-temperature ceramic materials are particularly needed on the leading edges of acute flight surfaces to withstand the intense heat that will be generated as these vehicles dip in and out of the upper atmosphere (in the region known as the exosphere) at speeds of Mach 5 and above. Similar materials will be need in the propulsion engines under consideration, such as the scramjet engine they mention. Although the Space Shuttle is technically a hypersonic vehicle, the vehicles Hilmas and Fahrenholtz are working on are very different. Unlike the bulky, blunt shapes found on a Shuttle, future hypersonic planes – envisioned for commercial and military use – will have a sleek design to minimize air resistance. Although this is still basic science stuff, Hilmas and Fahrenholtz have discovered an unexpected trove of previous research: Cold War-era data compiled by scientists in the U.S. and the former Soviet Union on nuclear research. The duo are still sifting through these old papers for clues about what to expect in the performance of new ultrahigh-temperature materials. 16 minutes. |