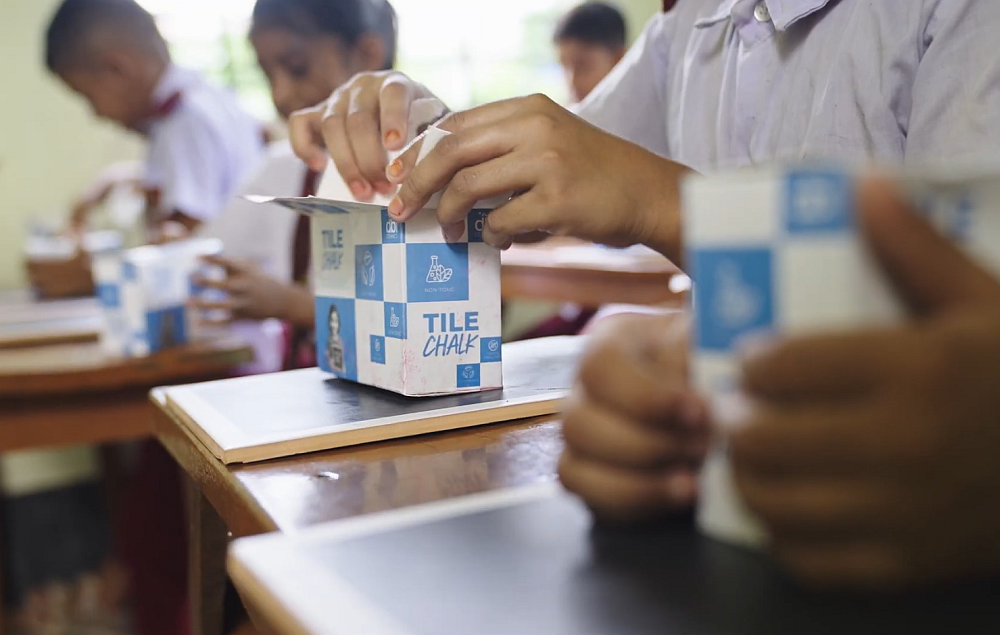

[Image above] Credit: Toby Smith; YouTube

Rare earth elements are often talked about in our world. But it’s usually the elements’ scarcity that takes center stage in conversation and makes rare earth recycling (here and here) a hot topic.

Rare earth elements are such a topic of conversation because of their ubiquity in today’s technology-dominated world. The group’s 17 elements are critical components in aerospace, defense, healthcare, clean energy, electronics, transportation, and chemical manufacturing applications.

According to the Rare Earth Alliance, “Because of their unique magnetic, luminescent, and electrochemical properties, these elements help make many technologies perform with reduced weight, reduced emissions, and energy consumption; or give them greater efficiency, performance, miniaturization, speed, durability, and thermal stability.”

Periodic table with rare earth elements boxed. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

And yet, despite their name, rare earths are not necessarily rare. Rather, most of the elements are not concentrated enough in deposits to be mineable. And even in higher-concentration deposits, the valuable elements are mixed with many others, so various processing and extraction steps are required to isolate rare earths.

It’s well known that China leads the world in production of rare earths, but what is less well known is the staggering environmental impact of rare earth production there. Processing rare earths often involves several rounds of solvent extraction in toxic, caustic chemicals like hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, or sodium hydroxide, generating a staggering amount of hazardous waste.

But let’s face it: It’s easy to ignore what’s hidden from view.

A group of architects, designers, writers, reporters, and thinkers called the Unknown Fields Division have traveled the world and are now pulling back the curtain to show the toxic story lurking behind rare earth production.

Unknown Fields is a self-described “nomadic design research studio that ventures out on expeditions to the ends of the earth to bear witness to alternative worlds, alien landscapes, industrial ecologies and precarious wilderness. These distant landscapes… are embedded in global systems that connect them in surprising and complicated ways to our everyday lives.”

The Division followed and documented the birth of modern tech components back to the source of rare earth elements. This journey took them to a city in Inner Mongolia called Baotou, which generates 70% of the world’s rare earth metal reserves.

Writer Tim Maughan traveled with the Division for part of the journey, which he described in a BBC article. “Everywhere you look, between the half-completed tower blocks and hastily thrown up multi-story parking lots, is a forest of flame-tipped refinery towers and endless electricity pylons. The air is filled with a constant, ambient, smell of sulphur. It’s the kind of industrial landscape that America and Europe has largely forgotten—at one time parts of Detroit or Sheffield must have looked and smelled like this.”

Beyond the industrial landscape, the centerpiece of the environmental distress caused by the industry is a 10 km2 tailings pond in Baotou where the refineries dump waste and processing byproducts.

From the images alone, the tailings pond looks like an alien landscape, completely devoid of life. Large pipes at the edges of this pond spew black sludge into the pond, spiking the soil there with three times the background radiation level present in the environment.

Credit: Toby Smith; YouTube

Watch the full Unknown Fields Division film, “Rare Earthenware” (6:42), here.

According to the Unknown Fields, producing 1 ton of rare earth elements also generates 75 tons of acidic wastewater containing acids, heavy metals, carcinogens, and radioactive materials. Considering that annual rare earth production reaches 100,000 tons, the industry generates 7.5 million tons of acidic wastewater every year.

“It could be argued that China’s dominance of the rare earth market is less about geology and far more about the country’s willingness to take an environmental hit that other nations shy away from,” Maughan writes for BBC.

While visiting the tailings pond, the Unknown Fields crew collected clay soil samples and brought them back home to the United Kingdom, where they fashioned the radioactive clay—carefully—into a set of traditional Ming vases.

Each vessel is created from the amount of waste generated in the production of a smartphone, laptop, and smart car battery, Unknown Fields says. A smartphone, which uses eight different rare-earth elements, creates 380 g of toxic waste; a laptop produces 1.22 kg of waste; and an electric car battery cell produces 2.66 kg of waste.

The project, including the vases and film, will be on display at the London Victoria & Albert Museum in the “What is Luxury?” exhibit, April 25–September 27.

View more images from the trip here from The Guardian and here at Unknown Fields.

Author

April Gocha

CTT Categories

- Electronics

- Environment