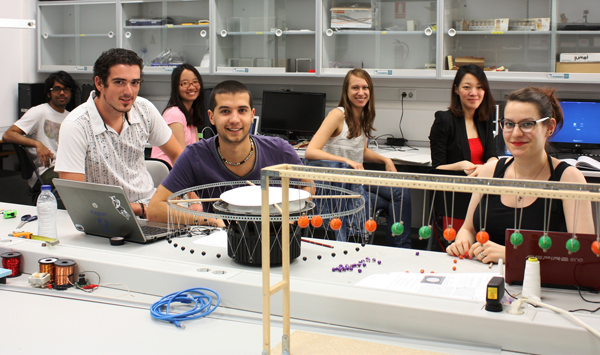

[Image above] Have efforts to create a more diverse STEM community worked? A new paper suggests that though some progress has been made, it’s not been enough to better represent underrepresented groups. Credit: Universitat Politècnica de València Campus de Gandia; Flickr; BY NC-SA 2.0

Over the years, universities, companies, and organizations (including ACerS) have poured a great deal of time, energy, and money into cultivating a more inclusive and diverse STEM community—and for good reason.

Humans are like snowflakes.

Just as no two snowflakes are exactly alike, no two humans are exactly alike. (At least, not yet.)

We each see the world from our own unique vantage point—each brings to the table our own unique experiences that color the world in our own unique way. Bring the strength of those snowflakes together and you have a blizzard that stands to impact the world in a mighty way.

It’s why diversity in any field—but particularly in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and math—lends itself to more effective problem solving and teams that are more innovative and productive.

So though no one would argue that a more diverse community is both desirable and needed, given the amount of time we spend talking about ways to better recruit and retain both minorities and women in the STEM fields—and the resulting action (or inaction)—what do “we” have to show for it?

According to a new paper in BioScience, not much.

Two biologists from Brown University, Andrew G. Campbell and Stacy-Ann Allen-Ramdial, analyzed the STEM pipeline and found that despite the “decades of efforts” devoted to developing a more diverse flow of scientists, engineers, technologists, and mathematicians, the groups that have traditionally been underrepresented remain underrepresented.

Though the pipeline continues to receive a steady flow of students, just as in a home repair gone bad, its backflows and leaks negate any forward progress.

“That pipeline we’ve laid? We’re stuffing it but the yield is less than we expect,” says Campbell. “That’s because it’s not a horizontal pipeline, it’s a vertical one. You can’t just stuff it and walk away.”

Their findings may appear deceiving in that, at first glance, it’s not all that bad.

An equal number (less than a third) of underrepresented minority (URM) and non-URM incoming college freshmen expressed an interest in STEM careers. The URM students, however, were less likely to graduate. In 2000, URM students made up 24.1 percent of U.S. college freshmen; in 2004, they represented only 18.5 percent of those receiving a bachelor’s degree.

The transition from undergrad to graduate program wasn’t any smoother. Statistics from the National Science Foundation reported in the paper show that in 2009, rather than move on to grad school or pursue a job in STEM, 36 percent of STEM-degree-holding URM students abandoned the field following graduation. Those who did enter the workplace were met with even less diversity. In 2010, URM individuals held only about 10 percent of STEM jobs in the U.S.

Regardless, in their paper, Campbell and Allen-Ramdial don’t just report the disappointing data—rather, they offer specific solutions for educators and policymakers to prevent pipeline backflows and leaks.

Solution 1: Alignment of culture and climate. Though we want to practice what we preach, when it comes to getting it done, the goals of fostering a more diverse culture are often at odds with the climate in which we work. They recommend regular (annual) and confidential surveys of staff with regards to the culture-climate alignment.

Solution 2: Partnerships between research and minority-serving universities. “The inconsistencies between successful undergraduate student performances documented in glowing reference letters and grades and the students’ subsequent poor graduate performance can be preempted by building interinstitutional partnerships that allow for curricular mapping of undergraduate courses onto graduate curricular training plans,” the authors write. Those partnerships also provide research exposure to students earlier and allow research faculty opportunities to “gain ‘cultural competence’ or familiarity with and understanding of URM students.”

Solution 3: Critical masses of minority students. Partnerships and focused recruiting are great, say the authors, but universities will most benefit from “critical mass” among URM groups (i.e., being able to identify with URM students from similar backgrounds). “What is critical mass [in a program]?” Campbell says. “That number is when students feel the greatest sense of belonging. It doesn’t have to be hundreds. It could be five.”

Solution 4: Faculty engagement in diversity. A culture can be created and a climate improved, but it needs feet to carry it toward success. Those feet need to include more than just senior administrators; specifically, the authors note “tenure-line professors can have a more lasting impact because of the uninterrupted longevity of their work. Faculty members should be incentivized to engage more deeply in diversity by making it a meaningful scholarly activity, alongside research and teaching,” they write. “The opportunity to formally report on diversity-related activities as part of annual review and reward criteria for merit and promotion should be established.”

Ultimately, the Brown researchers suggest that the goal isn’t just to attract URM students but to ensure they emerge from the pipeline as working scientists—and that to do so, the STEM status quo just won’t cut it.

“We’ve been doing the same thing and making the same investments for 30 years,” Campbell says. “The pipeline is the infrastructure. Some changes in the infrastructure need to be made.”

The paper is “Reimagining the pipeline: Advancing STEM diversity, persistence, and success,” (DOI: 10.1093/biosci/biu076).

If you’d like to be a part of those necessary changes, consider registering for the TMS Summit on Creating and Sustaining Diversity in the Minerals, Metals and Materials Professions 1 (DMMM1), July 29–31. An endorsing organization, ACerS will be well represented at the meeting.

To learn more about ACerS’s recently launched Ceramic and Glass Industry Foundation (CGIF)—a global partnership between industry and academia devoted to promoting ceramic and glass science, engineering, and technology, and ensuring that industry is able to attract and train the highest quality talent available—contact CGIF development director Marcus J. Fish.