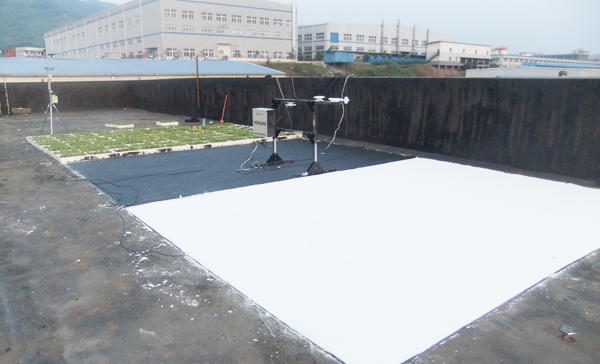

[Image above] A study of cool roofs in China found that their use would substantially reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions in regions where summer temps soar. Credit: Lawrence Berkley National Laboratory

Scientists from the Lawrence Berkley National Laboratory have previously established that cool roofs are the most cost-effective option for your pocketbook.

Now, a group from the lab, working with Chinese researchers, has shown that the use of light-colored roofs in China would “substantially” reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions in regions where summer temps soar.

According to a Berkeley Lab news release, the study—the first comprehensive one of its kind in China—tackled both residential and office simulations in seven Chinese cities in five climate zones and tested the use of cool roofs through short-term experiments in a Chongqing office building and Foshan factory.

“Cool roofs have been well demonstrated in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere,” says Ronnen Levinson, lead author and Berkeley Lab scientist, in the release. “While the concept is the same everywhere, we wanted to show that cool roofs would also be effective for Chinese construction, in Chinese climates, and with Chinese building operation practices.”

Their findings, published recently in Energy Policy, reveal that the use of cool roofs—which reduce heat flow as well as the need for air conditioning—in sultry areas south of Shanghai could not only reduce emissions of CO2, NOx, and SO2, but also lower annual energy costs.

For example, in Chongqing, Shanghai, Wuhan, and Guangzhou—four cities with particularly warm summers—office building roofs with an increased solar reflectance would save between $0.16 and $0.49 per square meter of roof. Residential energy costs are lower, so the savings would fall somewhere between $0.07 and $0.33 per square meter of residential roof.

Likewise, the simulations showed that cool roofs could reduce carbon emissions by 1.1 to 3.4 kilograms per square meter of roof in those four cities. A 1,500-square-meter cool roof on a small office building would save 5 metric tons of CO2 annually, which, according to the release, is about the same as taking a car off the road for the year. Equally harmful emissions of NOx and SO2 would be reduced by 2.9 to 13 grams per square meter, and 5.4 grams to 33 grams per square meter, respectively.

Levinson and team found that, even on the hottest summer day, the use of a white roof on the office building in Chonqing reduced air conditioning use by 9 percent. The A/C-less factory in Foshan still saw energy savings, with a decrease in indoor air temps by 1 to 3 degrees Celsius and a two-thirds reduction in roof heat flow. However, their findings do not advocate the use of cool roofs in cooler cities (Harbin, Changchun, and Beijing), where the “penalty” suffered in winter far outweighs summer savings.

Though Levinson believes the U.S. would experience similar energy savings, cool roofs could prove to be of greater impact in China, where wall area in sky-high cities outpaces roof area per person.

“In China there’s more wall area than roof area per person,” Levinson says. “Roofs get more sunlight per unit area, but walls have less insulation, so a cool wall can be as effective as a cool roof.”

Cool roofs and walls would also provide some added gains in terms of China’s air quality.

“Saving a unit of electricity in China has even greater benefit than in the U.S. because they emit more pollution per kilowatt hour,” he says.

Fewer pollutants would mean more sunlight, so, says Levinson, “as China takes steps to improve its air quality, the benefits of cool surfaces will increase because there will be more sunlight striking the building.”

The lab says that scientists will now begin year-round comparisons of black, white, and garden (green) rooftops in two Chinese cities and is helping their Chinese colleagues to create a natural exposure testing program that measures the roofs’ reflectance after withstanding soiling and weather.

The paper is “Cool roofs in China: Policy review, building simulations, and proof-of-concept experiments,” (DOI: 10.1016/j.enpol.2014.05.036).