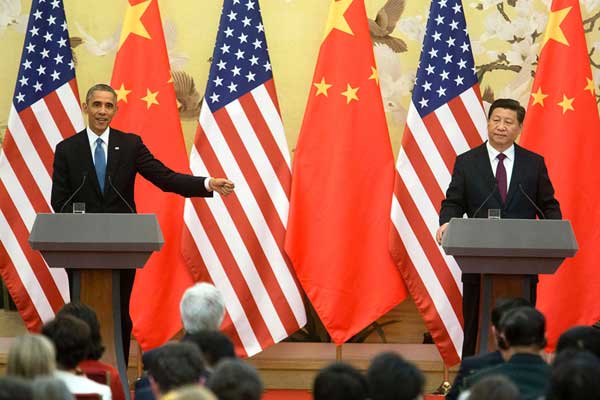

[Image above] President Barack Obama discusses his “ambitious” climate pollution targets during November talks with Chinese President Xi Jinping, who has issued his own targets as part of China’s “energy revolution.” Credit: The Official White House Tumblr; CC BY 3.0 US

During a trip to China last month, President Barack Obama met with Chinese President Xi Jinping to discuss numerous issues, including climate change.

China, the world’s top emitter, has relied heavily on fossil fuels and produces just under a third of all global carbon emissions, or 7.2 tons per person. (For comparison, the entire European Union only accounts for close to 10%; the U.S. accounts for 16%.)

But there are signs that the country is making steps toward a more permanent pollution solution.

The two leaders emerged from their November talks to announce that both countries were committing to reaching “ambitious” climate pollution targets—with the U.S. set to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2025 and China pledging to increase its use of zero-emission sources to 20 percent by 2030. The latter also agreed—for the first time—to peak its CO2 emissions, hopefully before 2030, as part of a broader plan to address issues of economics and air pollution, a call Xi has referred to as an “energy revolution.”

Obama declared the climate change announcement “a major milestone in the U.S.-China relationship. It shows what’s possible when we work together on an urgent global challenge.”

Now, new research from the Academy of Finland and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences shows that though China may be serious about its efforts to mitigate climate change, its demand for energy is more serious than ever before.

According to Jari Kaivo-oja, research director of the Finland Futures Research Centre, “From a global perspective, we’re seeing that China is channeling investments into renewable energy. While the growth in renewable energy capacity has been fast, the demand for energy has grown even faster, forcing China to further increase its coal power capacity.”

More coal means more emissions, and more emissions are due, in part, to China’s growing economy. Improvements in manufacturing and policy won’t be enough, Kaivo-oja says, to curb the increased demand resulting from a continued shift in consumer preferences and “rapid rise in affluence”—or to meet those 2030 targets.

“Our research shows that the ongoing structural change visible in the Chinese economy will only curb the growth in carbon emissions by 25 percent in comparison to the current economy, which is largely dependent on heavy industry,” he says. “At present, the plans for the development of the country’s energy system won’t help China cap its emissions by 2030.”

Whether or not China can meet their emission reduction goals, the country will have plenty of opportunities to at least attempt to reach the admittedly aggressive targets.

“China is a country still in the midst of a wave of urbanization,” says Kaivo-oja. “The infrastructure solutions in new urban areas and the consumer habits of a developing and increasingly well-to-do middle class are two issues that can significantly influence future developments. China has made huge investments in sustainable cities and in sustainable development exercises, which are all very positive signals from the viewpoint of sustainable energy and climate policy.”